For art lovers and wanderers alike, Paul Klee is a perfect companion: a violinist-turned-painter who turned colors into music, symbols into stories, and cities into lifelong inspirations.

A life in motion

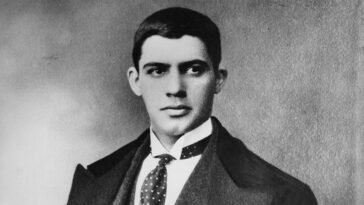

Paul Klee (1879–1940) grew up near Bern, Switzerland, in a musical family. He almost chose the violin before switching to art studies in Munich. The trip that changed everything came in 1914, when Klee travelled to Tunisia; dazzled by the North African light, he wrote in his diary: “Color and I are one. I am a painter.” From then on, color became the pulse of his work. After World War I he joined the avant-garde in Germany and, from 1921–1931, taught at the Bauhaus, where he wrote his famous color and form lectures. With the rise of Nazism he left Germany in 1933 and returned to Switzerland, where—despite illness—he produced an astonishing late burst of work before his death in 1940.

Art does not reproduce the visible; it makes visible.

– Paul Klee

Early Life and Travels (1879–1914)

Paul Klee’s story begins in 1879 near Bern, Switzerland, where he was born into a musical family. As a boy he learned violin and considered a music career, but painting ultimately stole his heart. In 1898 he left home to study art in Munich, Germany, absorbing lessons in drawing and imagination under painter Franz von Stuck (britannica.com). A formative trip to Italy soon followed, where the grandeur of Roman and Renaissance art left the young Klee both inspired and overwhelmed – he joked that “Humanism wants to suffocate me,” feeling a “long struggle lies in store for me in this field of color” . Back in Bern, he honed his craft with experimental etchings and caricatures that revealed a witty, if slightly sardonic, creative voice.

Klee’s wanderlust continued to shape his art. In April 1914, he embarked on a short journey that would prove life-changing – a two-week painting excursion to Tunisia with fellow artists August Macke and Louis Moilliet (3minutosdearte.com). There, under the blazing Mediterranean sun, Klee experienced a kind of artistic awakening. The North African light and colors dazzled him, unlocking a new understanding of color’s power. “Color has taken possession of me… Color and I are one. I am a painter,” he wrote in his travel diary, famously marking the moment he “discovered color” . This Tunisian epiphany gave Klee the vibrant watercolor palette and harmonic color “patches” that would characterize much of his later work, as he explored how hues could convey light, mood, and “luminosity and movement“.

The outbreak of World War I shortly after saw Klee drafted into the German army in 1916, though he was assigned to a relatively safe post and continued sketching even in uniform (zpk.org). After the war, his career blossomed. Klee joined the faculty of the Bauhaus in Weimar Germany in 1921 – an innovative art and design school – where he taught alongside Wassily Kandinsky and other modernist luminaries (artvee.com). Teaching did not slow his own creativity; if anything, the 1920s were prolific years. Ever the traveler, Klee seized opportunities for artistic pilgrimage. In 1928 he journeyed through Egypt, where the sight of the Nile and ancient hieroglyphs left a deep imprint on his imaginationg. One can sense echoes of those Egyptian inspirations in his later abstract symbols and pictographic shapes, as if the desert’s timeless visuals blended into his artistic language.

By the 1930s, political turmoil intervened. The rise of the Nazi regime in Germany forced Klee to leave his teaching post in 1933; his work was derided as “degenerate” by the authorities, and over 100 of his pieces were seized from German museums. Klee fled back to Switzerland, returning to his hometown of Bern with his wife Lily. Though illness (scleroderma) struck him in his final years, his creativity burned bright to the end – incredibly, he produced over 1,200 works in 1939 alone, as if racing against time. He died in 1940 in Locarno, Switzerland, just days before his Swiss citizenship was finally granted. Klee’s life journey thus spanned countries and continents, from the serene Swiss Alps to the glow of the Tunisian desert, and each place left its mark on the artist’s soul. For art lovers and travel enthusiasts alike, Klee’s biography reads almost like an itinerary of inspiration – every destination a new chapter in his “colorful” journey.

A Unique Artistic Style – Color, Symbols, and Playful Abstraction

Klee’s art is often described as highly individual and hard to classify. Instead of painting what the eye plainly sees, he painted what felt true to him – inner emotions, musical rhythms, and symbolic stories. One of the first things viewers notice is Klee’s inventive use of color. After 1914, color became the lifeblood of his art. He developed a signature palette of luminous hues often arranged in mosaic-like patterns or delicate washes. Klee believed colors could harmonize like notes in music, and he wrote extensively on color theory during his Bauhaus years (his famous Paul Klee Notebooks are considered as influential in modern art as Leonardo da Vinci’s treatise was in the Renaissance. In his paintings, warm and cool tones often play off one another to create mood – from the “intense light” of the Mediterranean captured in soft watercolor squares to the subdued twilight blues and browns of an evening scene (slam.org). He had a remarkable ability to make colors sing: sometimes vibrant and joyful, other times muted and mysterious, always chosen with care to evoke feeling.

Beyond color, symbols and abstraction are central to Klee’s style. He had a playful imagination and a love of the whimsical; his works are filled with quirky pictographs, childlike figures, and dream-like landscapes emerging from abstraction. Klee once said, “Art does not reproduce the visible; rather, it makes visible,” and his paintings often give form to the invisible—emotions, music, spiritual ideas—through simplified shapes and signs. He might turn a fish, a moon, or a person into a few sparse lines or geometric forms. This symbolic abstraction invites the viewer to participate with their own imagination. For example, a grid of colors might suggest “musical notes or sound vibrations, transmitting the idea of sensations rather than defined images,” as one description of his work Ancient Sound observes (kuadros.com). In Klee’s universe, a line “going for a walk” could become a whimsical creature; a patch of color could hold the resonance of a feeling.

Crucially, Klee’s art retains a playful, almost childlike spirit. He was fascinated by the purity of children’s drawings and primitive art, which he felt had a directness adults often lose. His works reflect this with their fresh, unfettered perspective – what one scholar called Klee’s “sometimes childlike perspective” and dry humor shining through. A piece like Twittering Machine (with its mechanical birds) or Senecio (the famous canvas resembling a child’s face) shows Klee’s sly wit and love of fantasy. Even when he tackles serious themes, there is a gentle whimsy in the way he composes forms. As an accomplished violinist, Klee also infused musicality into his art. He spoke of polyphony and rhythm in painting; many artworks have a harmonic structure (repeating motifs, balanced compositions) akin to a musical score. The end result of all these elements is an artistic style that feels alive and organic – abstract yet deeply human. Klee’s paintings may be small in scale, but they contain entire imaginative worlds. They invite us to feel as much as to see: to sense color like a melody, to read symbols like a poem, and to find joy in the act of looking.

In the Company of Movements and Fellow Artists

Though Paul Klee is often labeled a lone visionary, he was very much engaged with the artistic currents and communities of his time. In fact, one of Klee’s strengths was bridging various art movements while maintaining an independent voice. Early in his career, Klee found camaraderie with the Expressionists. In 1911 he met members of Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) group – artists like Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, and August Macke – whose bold use of color and emotional expression resonated with him. He exhibited 17 works in the second Blue Rider show in Munich in 1912, signaling his emergence in avant-garde circles. That same year he traveled to Paris and visited Robert Delaunay, absorbing the fragmented forms and prismatic colors of Cubism and Orphism firsthand. These influences (the Expressionists’ spirituality and the Cubists’ abstraction) would blend into Klee’s own approach.

Klee never officially joined one particular “-ism,” however. He preferred to chart his own course, drawing from many sources. In the 1920s, he became a key figure at the Bauhaus, the revolutionary German school of modern art and design. Invited by architect Walter Gropius, Klee taught at the Bauhaus from 1921 to 1931, alongside artists like Kandinsky, Lyonel Feininger, and László Moholy-Nagy. In Weimar and later Dessau, Klee and Kandinsky were not only colleagues but close neighbors and friends – they lived in twin faculty houses and no doubt had many exchanges of ideas over those years. At the Bauhaus, Klee nurtured the next generation with his lectures on form and color, becoming an influential art theorist. His presence linked the Bauhaus’s functional modernism with a more lyrical, spiritual strain of abstract art.

Meanwhile, the Surrealists in Paris admired Klee’s dream-like imagery. Although he was older than many Surrealist artists, Klee’s ability to make the subconscious visible through symbols earned their respect. In 1925 he took part in the first Surrealist exhibition in Paris, displaying his work alongside Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Pablo Picasso, and others. André Breton and his circle saw Klee as a kindred spirit in exploring imagination without boundaries. Klee also became part of the “Blue Four” group – a small ensemble formed in 1924 by art dealer Galka Scheyer to promote modern art in America. The Blue Four consisted of Klee, Kandinsky, Feininger, and Alexej Jawlensky, whose works toured U.S. galleries and brought Klee’s art to new audiences abroad. Through these connections, Klee was both a contributor to and a product of the rich network of early 20th-century modernism.

Yet for all these associations, Paul Klee remained uniquely himself. He blended influences from Expressionism, Cubism, Constructivism, and Surrealism into an art that defies tidy labels. As the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern notes, he “developed an independent position and never joined any particular art movement,” even as he followed the trends of his time with keen interest. This independence is part of why his work feels so timeless and personal. Klee also formed friendships across disciplines – not just painters, but musicians, poets, and thinkers – which enriched his perspective. Tragically, the Nazi denunciation of Klee in the 1930s cut short his public presence in Europe, but by then his influence had already spread internationally. His ideas traveled via students and exhibitions, inspiring later abstract artists (including the New York Abstract Expressionists) and even musicians and writers who found kinship in his harmonization of art forms. Klee’s legacy is one of quiet but profound impact. As one biographer put it, Klee became “one of the foremost artists of the 20th century”, and his thinking and work influenced subsequent generations worldwide. Whether through his teachings, his writings, or simply the example of his enchanting art, Paul Klee ignited creative sparks that are still felt in the art world today.

Three Masterpieces and Their Stories

To truly appreciate Klee’s genius, let’s explore the backstory of three notable paintings – artworks so evocative that they have been hand-picked for Prints & Spirit’s wearable art collection. Each piece reflects a different facet of Klee’s style and life experience, yet all three carry the artist’s unmistakable fingerprint of color, symbolism, and imagination.

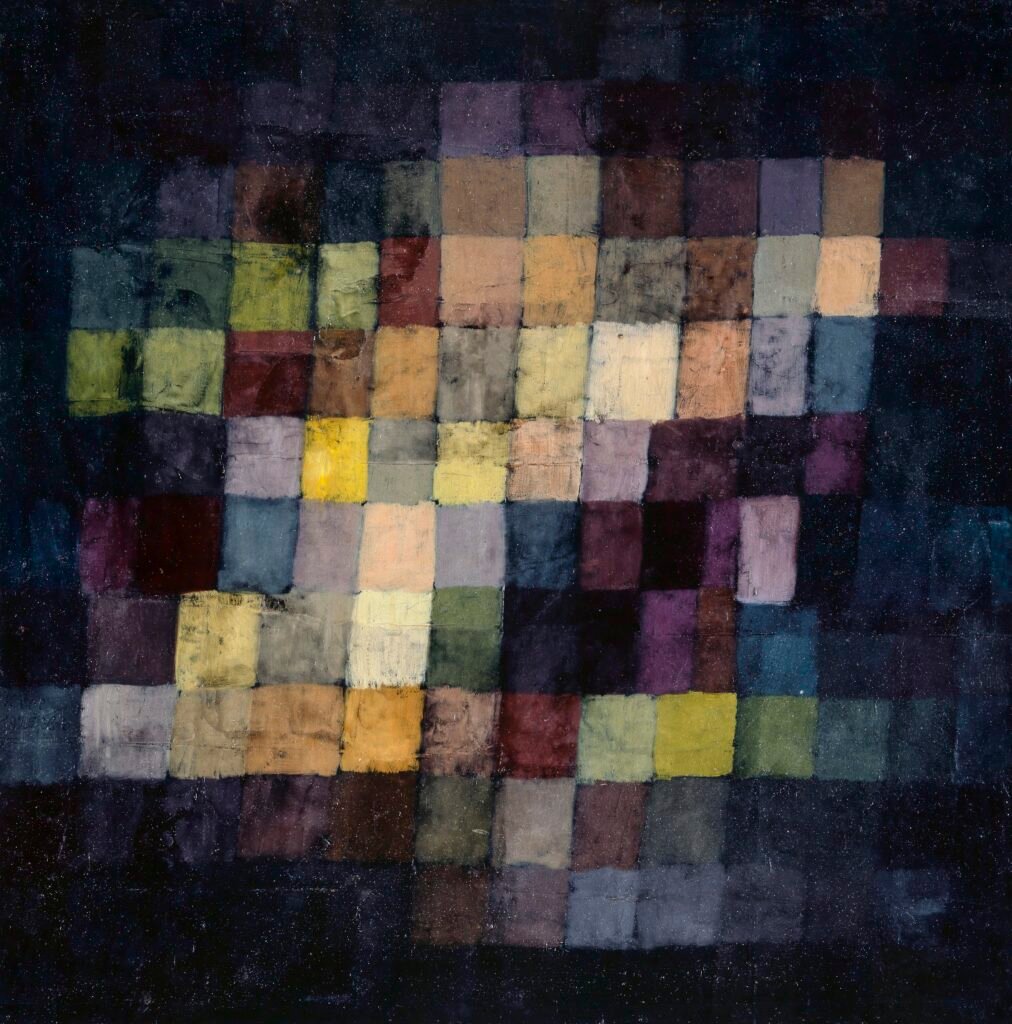

“Ancient Sound” (1925)

Klee painted “Ancient Sound” (original German title Alter Klang) in 1925, during his tenure at the Bauhaus. At first glance, the painting appears as a checkerboard of muted tones – a patchwork of soft reds, greens, blues, and yellows against a deep black background. The forms are abstract little squares or rectangles, almost like a musical grid. In fact, the composition is often likened to a visualization of music. The black background acts like the silence of a nighttime stage, making the colored notes pop forward in contrast. Those warm, earthy color blocks seem to vibrate on the dark canvas, creating a gentle rhythm for the eyes. It’s as if Klee was painting an “ancient sound” – a resonance from the past – using only color and shape instead of audible notes.

Despite having no literal figures, Ancient Sound feels alive with motion and energy. The clustered squares can be interpreted as musical notes or sound waves, pulsing in a kind of visual harmony. Klee, who loved music, often sought to merge the auditory and visual arts, and here he achieves a kind of synesthesia – you can almost hear the colors. Art critics have pointed out that the painting suggests an “intrinsic musicality,” a poetic hint that sound and sight are intertwined. The warm tones (ochres, rust reds, mossy greens) against black also give the work a mysterious, spiritual aura, as if we’re witnessing something elemental and universal. Klee’s choice of title, Ancient Sound, furthers this impression – inviting us to imagine a primordial melody echoing from the canvas.

The story behind this artwork connects to Klee’s experiences in the 1920s. By then, he had traveled, taught, and experimented extensively, and he was deeply interested in the idea of art as a bridge between senses and emotions. In his Bauhaus lectures, Klee spoke of a “visual music” and the importance of feeling in art. Ancient Sound embodies those ideas: it’s abstract, yet emotionally resonant. Some have even suggested that the painting hints at synesthesia, the blending of senses (seeing sound, hearing color). The colored mosaic might represent musical chords or the “summary” of a complex sound on a black backdrop. The emotional undertone is introspective – viewers often describe feeling calm or contemplative in front of it. There is no single narrative here; instead, Klee provides a space for the imagination. Much like listening to a piece of classical music, each person might envision their own scenes or memories when gazing at this visual melody.

“Late Evening (Looking Out of the Woods)” (1937)

The painting “Late Evening (Looking Out of the Woods)” captures a very different mood – that fleeting hour of dusk when day transitions to night. Klee created this work in 1937, after he had returned to Switzerland from Germany. It was a turbulent period (he was in exile and in declining health), yet this piece exudes tranquility and mystery rather than chaos. As the title suggests, Late Evening invites us to imagine standing at the edge of dark woods at twilight, peering out at the last light of day. Fittingly, Klee composed the image with an ultra-simplified palette: essentially two colors close in tone. The painting consists of organic indigo-blue shapes floating on a brown-violet field, like abstract shadows of trees against the dim sky.

Klee was intrigued by how evening light affects perception – how colors bleed into each other when the sun goes down. In this piece he explored that idea by limiting himself to blue and brown, which in the dusk appear almost as tonal inverses. The result is a delicate balance of positive and negative space: the brown forms suggest tree trunks or forest darkness, while the blue could be the evening sky peeking through, or perhaps the gathering night itself. The shapes are amorphous, rounded, and drift across the scene without clear outlines. There is a feeling of quiet and stillness, as if the woods are hushed at sunset. One poetic description calls the painting “a mesmerizing interplay of indigo shapes drifting across a dusky plum field – like silent symbols emerging from shadow.” Indeed, the blobs of blue on the muted purple-brown background have a hieroglyphic quality, as though nature is speaking in its own soft symbols.

The backstory here also reflects Klee’s state of mind. By 1937, Klee was battling illness and living in relative isolation in Bern. Late Evening can be seen as an introspective work – perhaps a meditation on twilight not just in nature but in life. The simplicity of the composition belies its emotional depth. Klee “skillfully balances” the dark and light elements, suggesting both the closure of day and the promise of night’s imagination. There is no bold color splash or playful creature here; instead, we get a moody minimalism that is almost modernist in spirit. Yet, typical of Klee, it remains deeply personal and poetic. The painting seems to ask the viewer to embrace the unknown gently: the woods are dark but not threatening, the sky is dim but not gone. It’s a reflection on transitions – those moments of ending that are also beginnings.

“Ad Marginem (To the Edge)” (1930)

Klee’s Ad Marginem feels like a small, time-worn parchment charged with quiet magic. In the center, a deep red disk glows like a sun or sealed wax—steady, resonant, almost musical. Around it, the surface is abraded and mottled, with tiny linear signs and scratch-marks at the edges (the margins) as if figures and symbols are gathering just beyond the picture’s core. Klee varnished the watercolor to achieve that antique, velvety patina, making the image look unearthed rather than freshly painted.

The title means “at the margin,” and that’s exactly where the action seems to happen: at the thresholds between light and dark, symbol and silence, center and edge. It’s a meditation on focus and periphery—a red, heart-like pulse held within a fragile world of traces. If Ancient Sound translates music into color, Ad Marginem translates gravity and stillness into a minimalist emblem.

Reception, Legacy, and Rediscovery

Klee was widely shown in his lifetime—Europe, the U.S., the first Surrealist exhibitions—yet his influence owes as much to his teaching as to his exhibitions. The Paul Klee Notebooks became foundation texts for modern art education; his students carried the method worldwide. Postwar retrospectives (Tate, Centre Pompidou, MoMA) kept the conversation alive; the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern now anchors scholarship and rotating displays. Today, when artists talk about color as music, symbol as sentence, or drawings that “think,” they speak Klee’s language.

What Klee’s paintings do

- Color as music. After Tunisia, Klee treated color like harmony and rhythm—quiet chords, bright accents, shimmering counterpoints. Diaries of Note

- Symbolic abstraction. Instead of copying nature, he distilled it into signs: moons, fish, houses, paths, grids—images that feel both ancient and playful.

- A childlike, lyrical touch. Klee loved the directness of children’s drawings; his lines meander like a melody, turning into creatures, maps or memories.

- Cross-pollinated modernism. He drew from Expressionism, Cubism, Constructivism and Surrealism, yet remained unmistakably himself—more poet than propagandist. At the Bauhaus he mentored a generation; the Surrealists in Paris embraced him as a kindred spirit.

Friends, movements, circles

Klee’s circle included Kandinsky, Franz Marc and August Macke of Der Blaue Reiter; he showed 17 drawings in their 1912 exhibition. He later taught beside Kandinsky at the Bauhaus and appeared in early Surrealist shows in Paris. His gift was to stand at the crossroads—absorbing ideas, but always speaking in his own soft, precise voice. The Museum of Modern Art Zentrum Paul Klee (artsfuse.org)

Where to see Paul Klee—by city

Exhibitions rotate, especially for light-sensitive works. Always check the museum’s “On View” page.

- Berlin, Germany – Museum Berggruen (SMB) shows a core Klee focus (around 70 works) within its modern collection. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

- Düsseldorf, Germany – K20 (Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen) houses one of the largest Klee holdings (~135 works). sammlung.kunstsammlung.de

- Munich, Germany – Lenbachhaus features Klee within its Blue Rider holdings and modern collection. lenbachhaus.de

- Essen, Germany – Museum Folkwang includes Klee in Prints & Drawings and modern galleries. (Rotations vary.)

- Bern, Switzerland – Zentrum Paul Klee preserves the world’s largest body of Klee’s work and schedules rotating displays. Zentrum Paul Klee

- Basel, Switzerland – Kunstmuseum Basel (and the Emanuel Hoffmann-Stiftung) hold key Klee works, including Ancient Sound and Ad Marginem. Kunstmuseum Basel+1

- Paris, France – Centre Pompidou has staged major Klee retrospectives (e.g., Irony at Work). centrepompidou.fr

- London, UK – Tate Modern mounted the sweeping show Paul Klee: Making Visible; works appear across its modern displays. Tate

- New York, USA – Guggenheim and MoMA both present Klee in rotation; New York often features Bauhaus-to-Surrealism dialogues where Klee shines. (Check current displays.)

- Washington, DC, USA – National Gallery of Art holds dozens of Klees viewable online and intermittently on site.

- St. Louis, USA – Saint Louis Art Museum is the home of Late Evening (Looking Out of the Woods). Saint Louis Art Museum

Sources & further reading

- Zentrum Paul Klee biography and collection overview;

- Museum Berggruen collection focus (Berlin);

- K20 Düsseldorf Klee album;

- Tate Modern’s Making Visible;

- Centre Pompidou’s Irony at Work;

- Saint Louis Art Museum object record for Late Evening;

- Kunstmuseum Basel Sammlung

- Online records for Ancient Sound (Alter Klang) and Ad Marginem.

No products in the cart.

No products in the cart.