Nerves, night, and knife-sharp line—Kirchner carved the modern into wood and canvas, then fled the city’s fever for the cool light of the Alps.

For anyone who has ever felt a city thrum under their feet, Kirchner is a kindred spirit: a draughtsman who turned streets into psychology, wood into lightning, and mountains into silence.

A life in motion

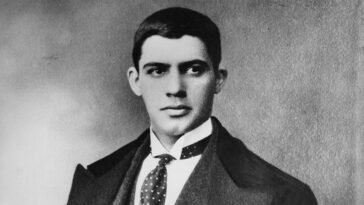

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938) was born in Aschaffenburg and raised in Chemnitz. Trained in architecture in Dresden and Munich, he chose art instead and, in 1905, co-founded Die Brücke, a small circle that rejected academic polish in favor of raw line and urgent color. In 1911 he moved to Berlin; there the metropolis—its crowds, cabarets, shop windows, and night trains—became his great subject. The First World War derailed him: he volunteered in 1914, suffered a breakdown in 1915, and recovered slowly. From 1917 he lived in Davos, Switzerland, where his style simplified and clarified. Branded “degenerate” by the Nazis in 1937, he died in 1938 near Davos.

Wir rufen alle Jugend zusammen! We call together all youth!

— from the Brücke manifesto (1906)

Early Years & Berlin (1905–1917)

Kirchner’s story begins with a studio-club above a Dresden shop: Die Brücke (Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Fritz Bleyl). They drew from life, revived the woodcut, and chased immediacy—friends as models, summers painting outdoors around the Moritzburg lakes and later Fehmarn, where Baltic light set his palette ablaze.

Berlin changed the tempo. Arriving in 1911, Kirchner roamed Friedrichstraße and Potsdamer Platz, sketching in cafés and trams. Back in the studio, he rebuilt memory into tilted scenes—sidewalks like conveyor belts, coats like blades, faces simplified to masks. The result was the legendary Street Scenes (1913–14): gliding couples that never quite touch, glamour edged with danger, color keyed to neon (acid greens, hot reds, indigo nights). Around Der Sturm he found allies and exhibitions; in his private life the dancer Erna Schilling became his partner and muse.

War snapped the wire. Kirchner volunteered in 1914, then spiraled into crisis. Self-Portrait as a Soldier (1915) stages the panic with a symbolic severed hand. In convalescence he returned to his most truthful medium—the woodcut—and produced the feverish color sheets for Peter Schlemihl (1915), printing from multiple blocks and letting color drift off-register so the image shivers like a memory.

From Berlin to the Alps (1917–1938)

Kirchner moved to Davos in 1917. The high, dry light and mountains pared his language down: where Berlin was jagged neon, Davos is emblem and breath—white against black, curve against void. He continued to cut and print his own blocks in small, variant runs, treating each pull as a performance. Public life grew harder in the 1930s; after confiscations and harassment, he died by suicide in 1938. The work remained: one of modern art’s clearest graphic voices.

A Unique Artistic Style — Cut Line, City Psyche, Alpine Emblem

Kirchner’s art is built from decision. The woodcut—ink, grain, and a single committed gouge—was his truth-telling tool. In Berlin he translated speed into tilted diagonals, social theater into masks, and electric light into acid chords of color. In Davos he stripped it back: black/white prints where two faces become a single sign, two curves a kiss. Even in paint, you feel the carver’s hand—edges that bite, bodies that move like strokes.

In the Company of Movements and Fellow Artists

Kirchner’s circle was small and intense. With Die Brücke, he helped set German Expressionism’s direction; their exhibitions were rough, immediate, and often scandalous. In Berlin he crossed paths with the Berlin Secession factions and the Der Sturm network; his friendships with models, dancers, and writers fed the pictures’ theatrical charge. After Brücke’s breakup (1913), he worked more independently, but the woodcut—Germany’s oldest graphic art—remained his link to tradition even as the images screamed of modern life.

How Berlin found him—and what it did to his art

When Kirchner arrived in Berlin (1911), the city was exploding: elevated trains, department stores, electric signage, cabarets and cafés stitched together by Friedrichstraße and Potsdamer Platz. He stepped into it like a live wire.

- The circle. He moved among writers, dancers, dealers and editors—Erna Schilling, a variety dancer who became his lifelong partner and muse; her sister Gerda; critics around Der Sturm; fellow Brücke member Otto Mueller; and the off-shoots of the Berlin Secession. Nights out were part reconnaissance, part ritual. He sketched or memorized scenes, then rebuilt them in the studio with sharpened diagonals and colliding color.

- Street Scenes (1913–14). These paintings and prints—women in high hats, men in topcoats, faces mask-like—turn the boulevard into psychology. Figures glide past without touching; desire and danger share a curb. Cropped viewpoints mimic photography and posters; tilted sidewalks and long black coats become vectors. The palette buzzes: scarlet cheeks against petrol blue, sulfurous greens spiking through violet dusk. Viewers aren’t observers; you’re in the stream, shoulder-brushing strangers.

- Woodcut = truth. Berlin sharpened his printmaking. He carved woodcuts like dispatches: quick, decisive, high-contrast. He usually printed them himself—in tiny, variant runs—so each pull feels like a performance. Posters, catalog covers, book illustrations: the same urgent cut shows up everywhere.

- The scene around him. Cabarets on the west side, cafés where editors and artists traded ideas, galleries like Der Sturm’s network shows (and the Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon moment), and the fractious politics of the Berlin Secession gave him both platform and friction. In 1913, his bitter history of the Brücke helped end the group—typical Kirchner: impulsive, uncompromising, allergic to institutions.

- Fall. He volunteered in 1914, collapsed by 1915. Self-Portrait as a Soldier (painted then) shows a severed painting hand—metaphor for a mind in panic. Hospital stays, medication, tremors. Yet even in crisis he carved and printed—hence the feverish Peter Schlemihl color woodcuts (your Agonies of Love sheet lives here).

Berlin gave him the vocabulary—speed, glare, collision. He carried it to the Alps.

What Kirchner’s art does

- Cuts feeling into form. The woodcut—ink, grain, and a decisive gouge—was his truth-telling tool.

- Turns city into psyche. Berlin’s speed becomes angular silhouettes and buzzing color; later, Davos distills to black-white symbols.

- Bridges old and new. Dürer’s graphic tradition meets modern anxiety; masks, folk carving, and “primitive” art echo through the line.

Key Works and Visual Style

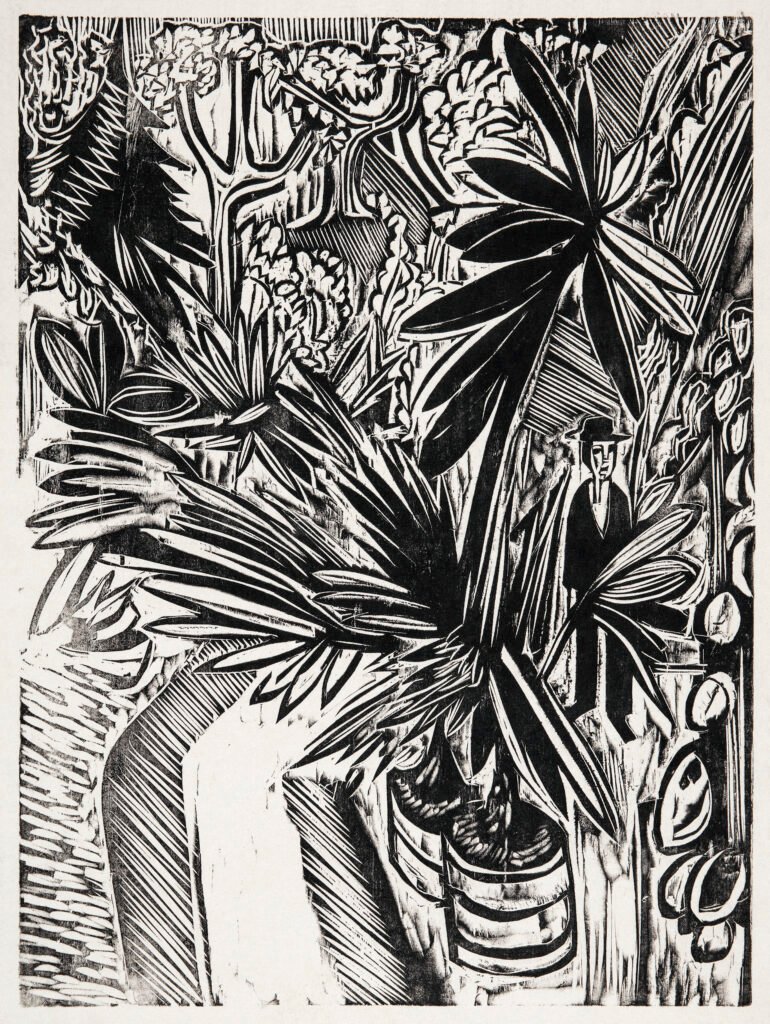

“Greenhouse (Jena)” (1914) — woodcut

A palm house seen through a storm of line: leaf veins, glass ribs, and humid air become black-and-white geometry. Kirchner’s knife doesn’t describe so much as charge—light splinters across fronds; negative space is as alive as ink. The subject ties to his 1914 Jena connections; the greenhouse motif pitches nature’s order against expressionist frenzy (smk.dk).

Why it matters: It shows how far a woodcut can go—drawing, architecture, and weather fused into one carved rhythm.

“The Agonies of Love” (from Peter Schlemihl), 1915 — color woodcut

A knot of figures in red and ultramarine, faces split, limbs spiraling: desire and pain printed like a fever dream. Recovering from his breakdown, Kirchner illustrated Chamisso’s Peter Schlemihl in 1915, often printing color from two blocks and letting pigments drift off-register—on purpose. The image looks carved and painted at once (nga.gov).

Why it matters: It’s Kirchner’s color woodcut at full voltage—raw psychology, theatrical color, and technical daring in one sheet.

Use on your page:

Alt: “Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, The Agonies of Love (Peter Schlemihl), 1915, color woodcut—interlocking figures in red/blue.”

Credit: National Gallery of Art, Washington.

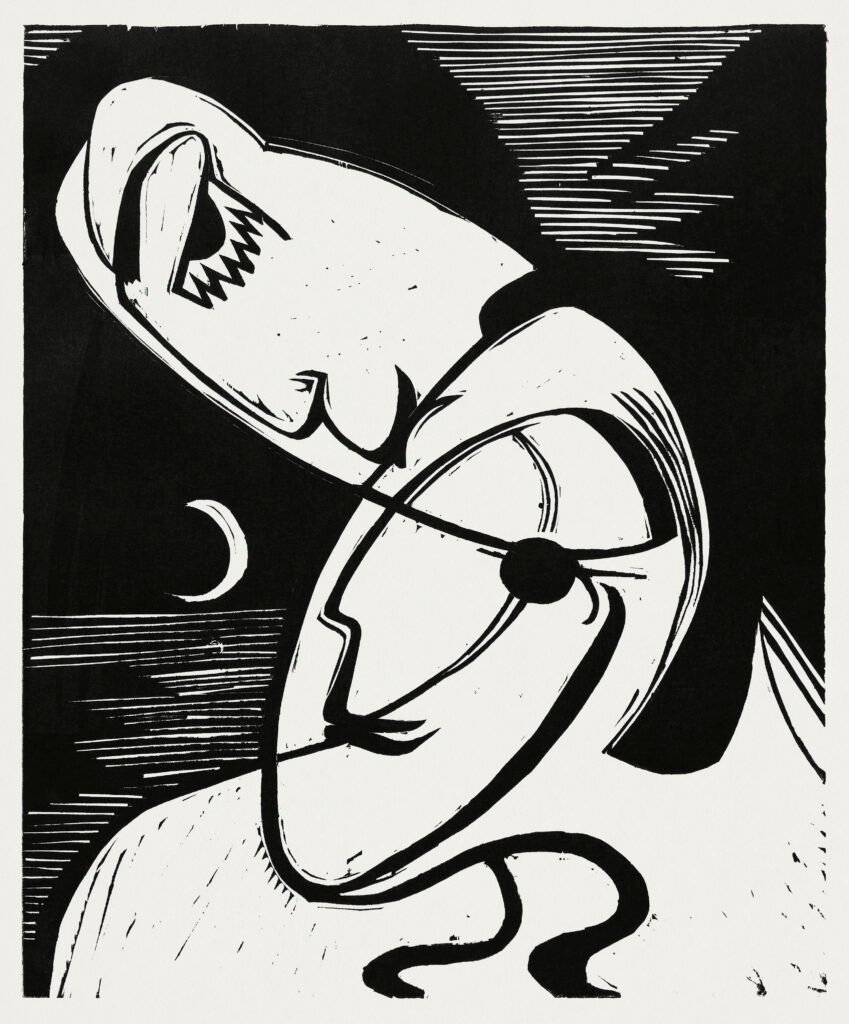

“The Kiss” (1930) — woodcut

Two crescent profiles fuse into a single white emblem against night-black. No crowd, no city—just curve, breath, and silence. Late Davos prints compress emotion to essentials; the chisel writes a lullaby. Multiple impressions exist (Kirchner Museum Davos; National Gallery of Art).

Why it matters: Proof that Kirchner’s intensity could turn tender—expressionism pared to archetype.

Reception, Legacy, and Rediscovery

Kirchner was infamous early (Brücke, Berlin), silenced mid-century (Nazi seizures), and reclaimed postwar by curators and print scholars. Today, the Brücke-Museum (Berlin) and Kirchner Museum Davos hold definitive archives; MoMA, NGA, and major German museums show his prints in depth (bruecke-museum.de; kirchnermuseum.ch; moma.org; nga.gov). His reputation rests not only on the Street Scenes but on the printmaking revolution he helped spark—proof that the woodcut can carry modern life’s speed and its quiet.

Where to see Kirchner—by city

- Berlin, Germany — Brücke-Museum (drawings/prints, archives); Neue Nationalgalerie (Street Scenes rotate).

- Davos, Switzerland — Kirchner Museum Davos (deep holdings from all periods).

- New York, USA — MoMA (prints, Street, Berlin).

- Washington, DC, USA — National Gallery of Art (major woodcuts including Schlemihl sheets and The Kiss).

- Copenhagen, Denmark — Statens Museum for Kunst (key woodcuts, including greenhouse imagery).

Sources & further reading

- Brücke-Museum (bruecke-museum.de);

- Kirchner Museum Davos (kirchnermuseum.ch);

- MoMA collection notes (moma.org);

- National Gallery of Art object records (nga.gov);

- Statens Museum for Kunst (smk.dk).

No products in the cart.

No products in the cart.