Brilliant, brief, and restless—Amadeo burned fast across the early 20th-century avant-garde, then came home to Portugal with Paris still humming in his colors.

Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso (1887–1918) grew up near Amarante in the north of Portugal and moved to Lisbon for studies before leaving for Paris in 1906. There, in studios and cafés around Montparnasse, he fell into a tight orbit with Modigliani, Brancusi, the Delaunays and other vanguard figures; Paris shifted him decisively from architecture to painting. – Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian

You can’t imagine how this land is full of color, joy, an intensity of spirit…

– Amadeo de Souza Cardoso

From Manhufe to Montparnasse (1887–1914)

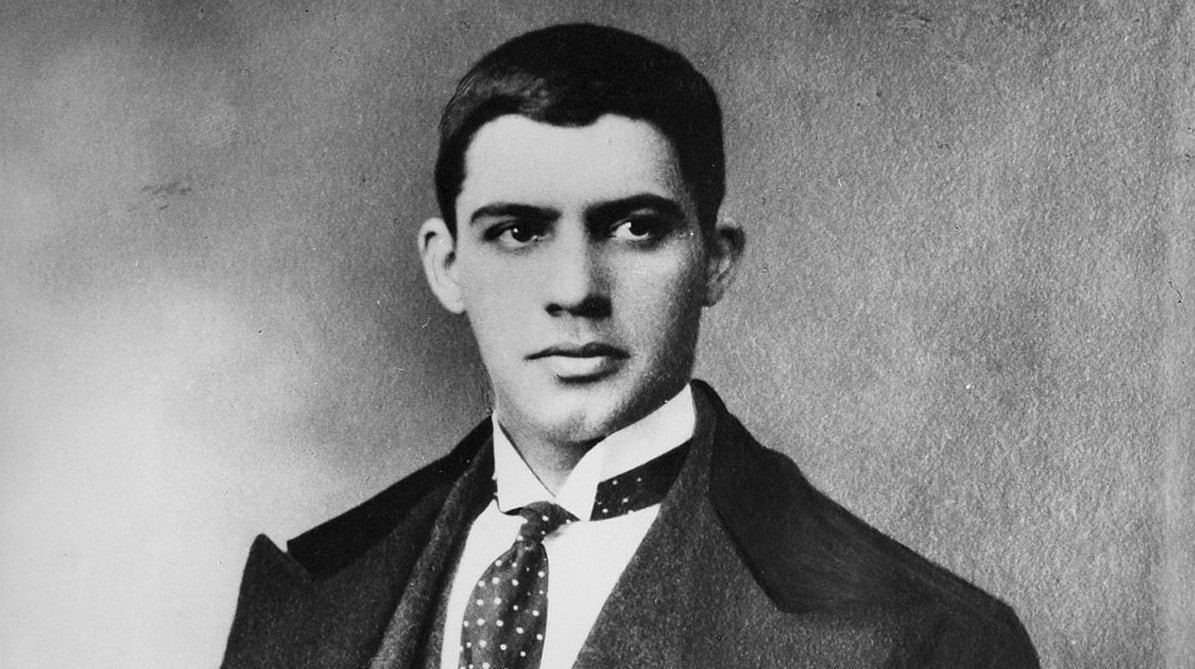

Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso was born in 1887 to a prosperous family in the rural parish of Manhufe, northern Portugal (en.wikipedia.org). Even as a teenager he felt a burning artistic destiny: “My destinies are unsettled but with me; with them I shall prevail, or for them I shall be crushed,” the 19-year-old Amadeo wrote defiantly to his parents (portoalities.com). In 1906, funded by his family’s comfortable means, he bid farewell to his mother and set off for Paris to “fulfil his destiny” in art’s world capital. He initially enrolled to study architecture, but Paris quickly seduced him away to painting and drawing. Settling in a Montparnasse studio (14 Cité Falguière), the young Portuguese immersed himself in bohemian circles of fellow émigré artists, honing his skills in caricature and illustration and abandoning architecture altogether.

In Paris, Souza-Cardoso blossomed amid the avant-garde ferment. He studied briefly at the Académie Vitti under Spanish painter Anglada-Camarasa and frequented Gertrude Stein’s circle (even moving his studio next door to Stein’s flat on the rue de Fleurus). By 1908 he had befriended artists like Amedeo Modigliani and Constantin Brancusi, sharing studios and exhibitions with them. He mixed easily with the international avant-garde – Sonia and Robert Delaunay, Juan Gris, Max Jacob, Alexander Archipenko, Gino Severini, Umberto Boccioni, and others were counted among his friends and influences (en.wikipedia.org, commons.wikimedia.org). It would “be a mistake… to frame Amadeo as a mere disciple” of these famous peers; art historians note that he stood in “the creative epicenter” of Parisian modernism, influencing others as much as they influenced him (portoalities.com). Restless and experimental, he absorbed Cubism, Futurism, Orphism, and Expressionism into a style unmistakably his own (redtreetimes.com). As one observer later wrote, he moved “seamlessly among [the movements] while maintaining his unique voice”.

By the early 1910s Souza-Cardoso’s talent was earning recognition. He debuted at the 1911 Salon des Indépendants with six paintings and continued to show in the Salon d’Automne from 1912 through 1914. In these years he feverishly produced work in different media: an album of 20 daring drawings (XX Dessins, 1912) won praise from critic Louis Vauxcelles, and he even hand-illustrated a Flaubert story in a lavish calligraphic manuscript. Ever savvy about advancing his career, Amadeo mailed portfolios of his drawings abroad to galleries in Germany, England, and America, sparking international interest. In 1913, at just 25, he achieved a breakthrough on the world stage. Thanks to his friend Walter Pach (an American curator), Souza-Cardoso secured a place in New York’s legendary Armory Show – the first great exhibition of European modern art in the U.S. He exhibited eight works alongside the likes of Matisse, Duchamp, Braque and others. His bold, vivid canvases were a surprise hit with American collectors: he sold 7 of the 8 works on view (making him the Armory Show’s third-best-selling artist). Chicago lawyer Arthur Jerome Eddy purchased several, later donating them to the Art Institute of Chicago. That same year, Souza-Cardoso’s paintings traveled to Berlin’s Herbstsalon (Autumn Salon) at Herwarth Walden’s Der Sturm gallery, and he even sent works to London (though a planned 1914 London show was halted by the outbreak of war). By 1914, the Portuguese youth in Paris had become a rising star of the avant-garde on two continents, described by one acquaintance as “an artist in the absolute meaning of the word.”

Homecoming, War, and Tragic Fate (1914–1918)

In the summer of 1914, on a holiday to Portugal, Amadeo was caught by the eruption of World War I and prevented from returning to Paris. What was expected to be a short disruption became a four-year exile in his homeland. He married Lucie Meynardi Pecetto, the young woman he had met in Paris years before, and settled back at his family’s estate in Manhufe. Initially cut off from the cosmopolitan art scene, Souza-Cardoso did not lapse into provicial obscurity – quite the opposite. The war years in Portugal saw him reach full creative maturity, experimenting boldly with new forms and techniques. He delved into collage and mixed media (anticipating Dadaist ideas), and his style, which had already explored abstraction and expressionist color in Paris, evolved in daring ways. In one late work, for example, he affixed real fragments of mirror and a perfume label to the canvas – a reflection of how far he was pushing beyond traditional painting (artsandculture.google.com).

Importantly, Amadeo’s “isolation” did not mean solitude. By 1915, an unlikely avant-garde enclave formed in Portugal when his friends Robert and Sonia Delaunay – refugees from war-torn France – took up residence in a village not far from Amadeo. Reunited with the Delaunays, and joined by Portuguese modernists like Eduardo Viana and poet José de Almada Negreiros, Souza-Cardoso stayed at the cutting edge of art. Together they even conceived a “Corporation Nouvelle” for international touring exhibitions of modern art, an ambitious project that ultimately fell victim to wartime difficulties. Amadeo also became a quiet catalyst for Portugal’s own modernist movement. He befriended members of the Lisbon-based Orpheu literary group (which included futurist poet Fernando Pessoa), contributing to the short-lived magazine Portugal Futurista in 1917. Though inherently independent – “I do not follow any school. Schools are dead. Am I a cubist, a modernist, an abstractionist? A bit of everything,” he declared – Souza-Cardoso aligned himself with the radical spirit of Futurism to jolt Portugal’s conservative art establishment (commons.wikimedia.org).

At the end of 1916, Amadeo took the bold step of presenting his work to the Portuguese public for the first time. He organized two large solo exhibitions of his paintings – one in Porto and then in Lisbon – showing an astonishing 114 works under the provocative banner “Abstraccionismo”. The reaction was dramatic. Accustomed to traditional art, local critics and audiences were bewildered (if not scandalized) by Souza-Cardoso’s wild colors and fragmented forms. The Lisbon press derided the show as “arte de loucos” – the “art of madmen” – and in one extreme incident a furious viewer even physically assaulted the artist in protest. Despite the backlash, Portugal’s small modernist community rallied to Amadeo’s defense: poet Fernando Pessoa and artist Almada Negreiros publicly praised him as the greatest painter of their generation, championing his right to artistic freedom. This episode was a testament to Souza-Cardoso’s uncompromising vision, as well as the cultural gap he was attempting to bridge between provincial Portugal and the European avant-garde.

Tragically, Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso’s brilliant ascent was cut short just as the war was ending. In October 1918, the artist contracted the raging influenza pandemic (the Spanish flu) and died within days at the coastal town of Espinho at the age of only 30. His sudden death extinguished a “short and intense” career that had already staked a claim in modern art’s revolution. Friends and family were devastated – Modigliani, upon hearing the news, is said to have wept inconsolably for the loss of his Portuguese brother-in-art. Amadeo left behind a substantial body of work (over a hundred canvases, plus drawings and writings) – work that was boldly in tune with the “aesthetic revolutions” of his time yet, as one scholar noted, “like nothing else” in its singular blend of influences.

Folklore and Modernity: Portuguese Influences in His Art

One hallmark of Souza-Cardoso’s art is the way it fuses the imagery of his Portuguese homeland with the avant-garde styles of modern Europe. Although he straddled two worlds – the “euphoric center” of Paris and the quiet village of Manhufe – Amadeo never abandoned the sights and symbols of his native culture. Traditional folk motifs and rural landscapes permeate his modernist canvases. He incorporated everyday rustic objects, snippets of folk song lyrics, and even the handmade dolls and musical instruments of Portuguese folklore into his compositions. The natural scenery of northern Portugal also appears frequently: rolling green hills, dense woods, winding rivers, and even imaginary castles inspired by local legends populate his paintings. His childhood home of Manhufe was both a real landscape and a “mental landscape” for the artist – a wellspring of imagery that he translated into modern art.

What makes Souza-Cardoso’s treatment of these themes so striking is that he mingled folk-traditional elements with the jarring new imagery of the 20th century. In his paintings, one can find mountains, farms, and regional costumes sharing space with speeding automobiles, whirring machines, and urban billboards. He did not see these as contradictory. Amadeo’s canvases create a “fusion of his home region and the vertigo of modern life,” freely mixing “rural and modern worlds” without hierarchy. For example, a composition might feature the silhouette of a Portuguese water mill or a folkloric minho doll alongside the forms of telegraph wires, electric light bulbs, or even snippets of advertising texta. Such juxtapositions were radical – they broke with academic art’s boundaries – yet in Souza-Cardoso’s hands they feel almost whimsical and dreamlike.

He was, in a sense, building visual “bridges” between Portugal’s past and the cosmopolitan present.

His palette could shift from the earthy tones of village life to the “dazzling, non-naturalistic color” of modernist abstractionartera.aeartera.ae. This bold synthesis of folklore and futurism gave Amadeo’s work a unique flavor among the avant-garde. Where Italian Futurists exalted machines alone, and French Cubists analyzed form for form’s sake, Souza-Cardoso was equally enamored of a rooster from a village fair or the lyrics of a folk song – and he immortalized them with the same daring fragmented brushstrokes that he used to depict an automobile or aeroplane. Art historian Robert Loescher later dubbed him “one of early modernism’s best-kept secrets,” precisely because his work defies easy categorization, weaving the Portuguese soul into the fabric of international Modernism.

Key Works and Visual Style

The Stronghold (1912)

Symbolically, this painting can be read as an homage to Portugal’s historic castles and coastal villages, transformed by Amadeo’s modern eye. He often drew inspiration from the medieval castles dotting the northern Portuguese landscape (sometimes calling such works simply “O Castelo”). Here, the “stronghold” might stand for the idea of home or refuge – a sturdy symbol of tradition – even as its form is deconstructed into modernist geometry. Notably, The Stronghold was one of the works that Souza-Cardoso sent to the 1913 Armory Show in the United States (artintheperiphery.wordpress.com). American viewers, who had never heard of the young Portuguese, were captivated by its enigmatic charm; it sold quickly at the exhibition. Today the painting resides in the Art Institute of Chicago, which acquired it from Arthur J. Eddy’s collection in 1931 (artsy.net). In Chicago’s catalog it is described as a “painting of [a] town and bay filled with ships composed of geometric shapes”artic.edu, highlighting the work’s playful semi-abstraction. Formally, Amadeo’s brushwork here is relatively smooth and the forms are sharply defined, almost like facets of cut stone or crystal. He employs a limited palette of bluish-greys, white, touches of forest green and sandy brown – perhaps suggesting moonlight on granite walls and the green countryside beyond. The Stronghold thus showcases Souza-Cardoso’s ability to marry local imagery (fortified towns, rolling hills) with the visual syntax of Cubism. It stands as a pictorial “bridge” between worlds, much like the arch spanning the canvas: on one side lies the regional past (the castle), and on the other, the modern future (the painting’s radical style). Little wonder that nearly all of Amadeo’s canvases at the Armory Show, The Stronghold included, were snapped up by collectors – they were at once radically new and strangely evocative of something timeless (artsy.net).

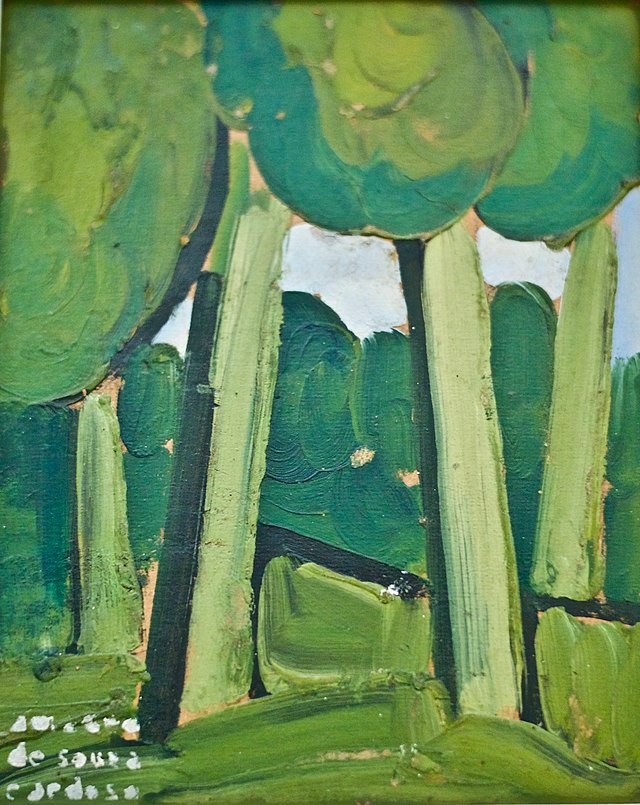

Green Landscape (c.1914)

Despite its modest size, Green Landscape carries symbolic weight. Created around the time Amadeo resettled in Portugal due to WWI, it may represent his reconnection with the Portuguese countryside – the green hills of home that contrasted so sharply with Paris’s urban bustle. The almost monochromatic green palette evokes the intense greenery of Minho (the northern region famous for its “green wine”), where Amadeo wandered. In simplifying the scene to basic forms, Souza-Cardoso shows an affinity with Expressionism and even hints of Fauvism (the bold use of non-natural color). Yet the mood is calmer than the wild Fauves – here greens are harmonious, layered in serene tonal variations, creating a meditative rhythm of tree shapes. The painting contains virtually no sharp angles or broken facets as seen in his cubist works; instead, it’s all curved organic shapes, suggesting softness and growth. This reflects another side of Amadeo’s art: he could be fiercely avant-garde, but he also had a poetic sensitivity to nature’s simple motifs. In Green Landscape, the folkloric influence is subtler than in his collage works – it lies in the choice of subject (a quiet forest scene typical of northern Portugal) and in the honest, almost naive directness of the depiction. At the same time, the piece remains thoroughly modern in execution: the flattened perspective and the freedom of the brushstrokes (not blending or shading realistically, but laying down pure fields of color) align with contemporary trends in European painting. We might consider Green Landscape a small homage to his roots – a piece that “contains what the artist felt to be his: a natural landscape but also a mental one.” It’s as if Amadeo distilled his memory of Portuguese forests into an abstracted memory-painting, using green not just as a color of leaves, but as a symbol of life, renewal, and homeland.

The Green Eye Mask (Head) (1914–1915)

Visually and emotionally, The Green Eye Mask is powerful. It exemplifies Souza-Cardoso’s engagement with Expressionism, as it conveys a raw psychological depth through color and form. The asymmetry of the eyes – one a void, one vividly green – gives the face a haunting, uncanny quality. Green is traditionally associated with illness or the supernatural (“green-eyed” can mean jealous or even demonic in folklore), and here the single green eye stares out like an otherworldly insight or “insight of illness,” depending on one’s reading. The entire head resembles a ceremonial mask – calling to mind both the African masks that influenced Picasso and others, and the folk masks of Portuguese festivals (where painted wooden faces are worn in carnivals). By titling it “Mask, Head,” Amadeo suggests it is both a living head and a mask – a persona that both reveals and conceals. This duality might symbolize the idea of the self vs. the facade, a theme resonant in modern art (many modernists were fascinated by masks as symbols of identity). Formally, Souza-Cardoso constructs the head with angular planes akin to Cubist portraiture, yet the fiery emotive color aligns more with Fauvism/Expressionism. The paint looks almost “sculpted” onto the surface in parts, giving a tangible relief to features like the brow and nose. Indeed, contemporaries noted that Amadeo was often “the inventor of forms” even among his circle – here he invents a form that is half-painting, half-sculpture (the embedded materials and textured layers make the canvas itself object-like).

Contextually, The Green Eye Mask was created during the war years when Amadeo was back in Portugal, and it hints at the anxieties and creative fervor of that time. One could imagine that this unsettling face reflects the angst of a world at war or the artist’s own sense of isolation. Yet it also ties back to Portuguese cultural motifs: masks and heads appeared in local folk art and religious processions. By transfiguring a head into a kaleidoscope of color, Souza-Cardoso was effectively bridging the gap between the “primitive” art of masks and the most advanced pictorial ideas of his era. As an experimental piece, Green Eye Mask also shows Amadeo flirting with mixed media – similar works from 1915–16 saw him incorporate collage elements (for example, in a related piece often just called Cabeça (Head), he included reflective materials). This painting does not have obvious collage, but the layered, broken surface almost suggests it. Such techniques place Souza-Cardoso on the cutting edge, parallel to the likes of Picasso’s synthetic Cubism or the Dada collages – yet his inspirations were distinctly his own. The result is an image that is both viscerally human and eerily mask-like, inviting viewers to ponder what lies behind the “green eye” and cracked paint – perhaps a statement that in the modern age, as in folklore, our true selves are often hidden behind constructed masks.

Reception, Legacy, and Rediscovery

Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso’s lifetime was brief, but in those years he experienced both enthusiastic acclaim and baffled rejection. Internationally, he enjoyed early success – he was lauded in Parisian art circles, sold well in America in 1913, and was seen as a promising bridge between Portugal and the avant-garde. However, in his home country his radical art was met with resistance (as seen in the scandal of the 1916 exhibitions). When he died in 1918, the shock and sorrow were soon followed by a long period of obscurity for his work. A posthumous retrospective in Paris in 1925 (with 150 works) was well-received, suggesting that had he lived, Amadeo might have joined the pantheon of modern masters. In Portugal, a “Souza-Cardoso Prize” for modern painters was established in 1935, honoring his pioneering role. But the mid-20th century was not kind to Amadeo’s memory on the world stage. Several factors led to his work essentially vanishing from the mainstream narrative of modern art: for one, his widow Lucie guarded his remaining paintings closely and “resisted sharing [them]” for decades. Not until the 1980s did she finally donate a large collection of his art and papers to the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon. Additionally, many of Amadeo’s works stayed in Portugal (some in the tiny Amarante museum that bears his name), during a time when Portugal itself was under an isolationist dictatorship This meant that for much of the 20th century, “the silence of Portugal…did not allow the international historical update of the artist”, in the words of one historian (en.wikipedia.org). In short, Amadeo became a local legend – revered by Portuguese modernists as a trailblazer – but remained virtually unknown abroad, absent from the standard textbooks of modern art which tended to focus on Paris, New York, or London.

It wasn’t until the 1950s that a flicker of renewed interest appeared. In 1952 the Amarante Municipal Museum (housed in a former convent by the Tâmega River) dedicated a room to Souza-Cardoso’s work, reintroducing him to the Portuguese public. A major retrospective in 1958 in Lisbon helped solidify his status in Portugal, though internationally he was still a footnote. Over the subsequent decades, Portuguese curators and scholars – notably Helena de Freitas – worked tirelessly to answer the lingering question, “Who was Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso?”, and to gain him recognition beyond Portugal. The globalization of art history gradually caught up with him. In 2016, nearly a century after his death, Souza-Cardoso finally received a spectacular international spotlight: the Grand Palais in Paris held a blockbuster retrospective of his work, the first in Paris since 1925 (en.wikipedia.org, grandpalais.fr). Titled simply “Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso, 1887–1918,” the exhibition featured 150 of his works alongside pieces by his friends Modigliani, Brancusi, and the Delaunays. French critics and the public were astonished at this “forgotten” modernist who had in fact been at the heart of the avant-garde. (One Art Newspaper headline tellingly called him a “Forgotten Portuguese Modernist” getting his due at last artintheperiphery.wordpress.com.) The Grand Palais show – organized in partnership with the Gulbenkian Foundation – was a revelation, prompting many to agree with curator Laurent Salomé’s assessment that Amadeo was “no more a follower than an inventor” among his peers. The exhibition reestablished Souza-Cardoso in the international canon, leading to further showings and studies.

Today, Amadeo’s work is embraced as a missing puzzle piece of early modernism – a “best-kept secret” now uncovered. In Portugal, he is celebrated as a national cultural hero: the Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso Museum in Amarante holds many of his drawings and paintings, and the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum’s Modern Collection proudly displays his works (often juxtaposing them with contemporaries). For example, Gulbenkian’s 2007 exhibition “Amadeo de Souza Cardoso: Avant-Garde Dialogues” highlighted his connections to European art movements. The prestigious Art Institute of Chicago – thanks to those Armory Show acquisitions – remains a key repository of Souza-Cardoso’s art outside Portugal. Visitors to AIC can encounter “Le Saut du Lapin” (The Leap of the Rabbit, 1911), one of his joyful futurist-cubist canvases, still “exemplifying the unique style [he] developed while working in Paris”artic.edu. The Institute’s holdings, including The Stronghold and other pieces, keep Amadeo’s legacy alive in the context of global modern art. As critical re-evaluations continue, Souza-Cardoso is increasingly recognized as a multifaceted innovator whose work “lies at the crossroads of all the artistic movements of the twentieth century” (grandpalais.fr) – an artist who refused to be boxed into any single “-ism,” and who instead forged an art “between tradition and modernity, between Portugal and Paris.”

In hindsight, Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso’s life reads like a poignant what-if story in art history. He had only just begun to show the world the depth of his talent when fate intervened. But the artworks he left behind tell a vibrant story – one of a young man from a provincial wine country who carried his heritage to bohemian Paris, dazzling the avant-garde, then returned home to ignite a modern art revolution on his own soil. It’s a story of bridges: between old and new, local and international, painting and collage, joy and tragedy. After decades of obscurity, that story now is being told to a wide audience, and the name Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso is spoken alongside the great modernists he once knew as friends. In the end, the prophecy he wrote in youth – “with [my destinies] I shall prevail” – has come true in its own way. His destiny, unsettled but driven, has prevailed through the power of his art, which speaks to us with undimmed brilliance: the Portuguese modernist who was lost to time, now found again.

Sources:

- The Rediscovery artsy.net;

- Wikipedia en.wikipedia.org;

- Joana Leal in Gulbenkian Museum archives commons.wikimedia.org;

- Portoalities Blog portoalities.com;

- Muskegon Museum of Art muskegonartmuseum.org;

- Grand Palais (Paris) Exhibition Notes grandpalais.fr;

- Art Institute of Chicago Catalog artic.edu.

No products in the cart.

No products in the cart.